Writing down step-by-step instructions for preparing a culinary dish is not a new concept. According to Wikipedia, the earliest known recipes date from approximately 1600 BC and come from an Akkadian tablet from southern Babylonia.

Step-by-step procedures for calculations, algorithms, date back to the 9th century mathematician Al-Khwarizmi. Recipes and algorithms achieve the same goal in different contexts: they provide instructions to make a task replicable.

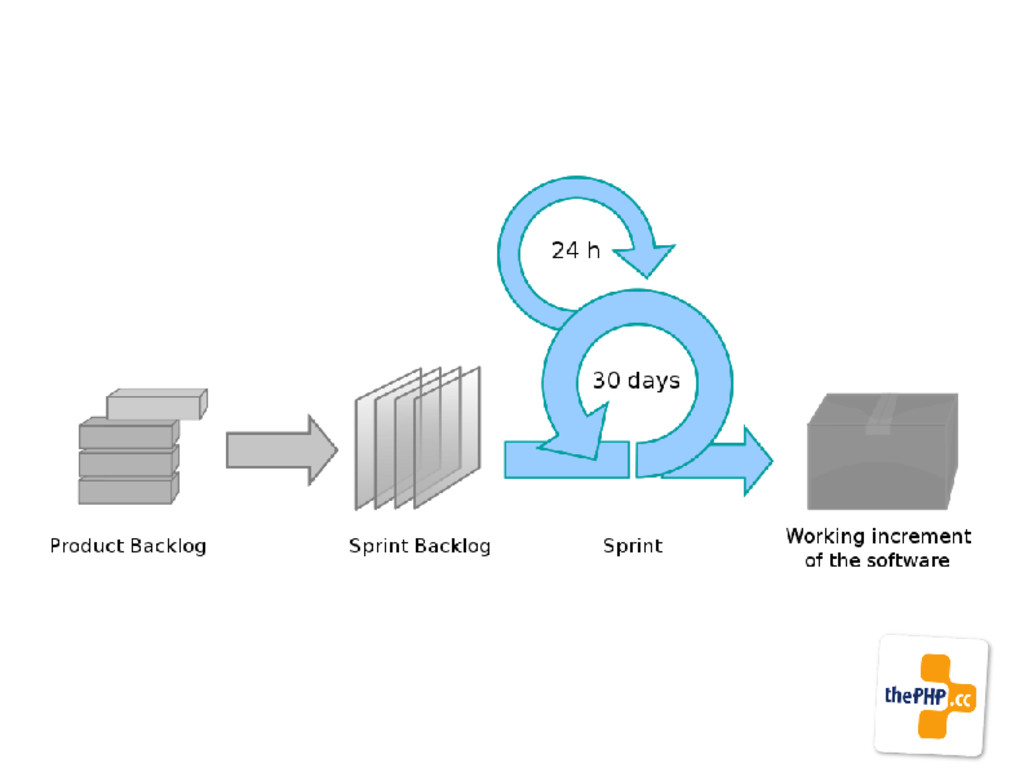

The members of a software development team pick and choose from a variety of methodologies to define their process: their replicable way of producing software.

The preparation of delicious culinary dishes has, at least metaphorically, more in common with the development of high-quality software than you may think.

As a professional cook, for instance, you want to keep your restaurant kitchen spic and span. Cleaning tasks such as brushing the grill between cooking red meat, poultry and fish have to be done several times a day. Grease build up is a major fire hazard. This is why grease traps should be cleaned out daily, sinks and faucets should be delimed weekly, and you should wash behind the hot line (oven, stove, fryers) every month.

These cleaning tasks take time. Time in which the kitchen staff prepares no food and generates no revenue.

Now imagine that the owner of the restaurant tells you to cut down the time your staff spends on keeping the kitchen clean. This may work in the short run. But in the long run you will get unfriendly visits from the health department. Or the grease catches fire, and your kitchen goes up in flames.

The software development world's equivalent to these cleaning tasks are activities such as refactoring the code to keep it maintainable and writing unit tests for it.

Imagine you are the chef at a restaurant that is known to serve the best steaks in town. You have earned your reputation based upon one guiding principle: never compromise. You hand-select the beef for your steaks at a butchery you trust, for instance. You passionately apply your experience and cook the steaks to perfection.

Now imagine that the owner of the restaurant tells you to buy your meats from the supermarket (and not just from the butchery at the supermarket but pre-packaged cuts from the refrigerated shelf) instead.

What do you do? Compromise? Or do you stand up to your boss telling him that quality is not negotiable?

This may well lead to a situation where Martin Fowler's famous quote applies:

If you can't change your organization, change your organization!

When you do not know where your ingredients come from you cannot be exactly sure what they contain. Cooking with these ingredients is not a problem as long as you do not serve people that have food allergies at your restaurant.

When you are not using fresh produce, herbs, and spices to prepare a tomato sauce, for instance, yourself you cannot serve an off-the-shelf sauce from the supermarket to a guest that is allergic to garlic, for instance, with good conscience. The label on the glass in which the sauce is sold may or may not list garlic as an ingredient. But just because it is not listed as an ingredient does not mean that the sauce does not contain traces of garlic; which may be enough to trigger an anaphylaxis.

It makes a lot of sense to use third-party components in the development of your software. However, when you use a component that is not (sufficiently) tested you run the same risk as the cook who uses an off-the-shelf sauce from the supermarket. You do not know exactly what the code of the component does. It may work fine for the "happy path". But what about the edge cases? Even worse is using a third-party component that is no longer maintained. It may work fine today. But will it still work when a new version of PHP, for instance, is released?

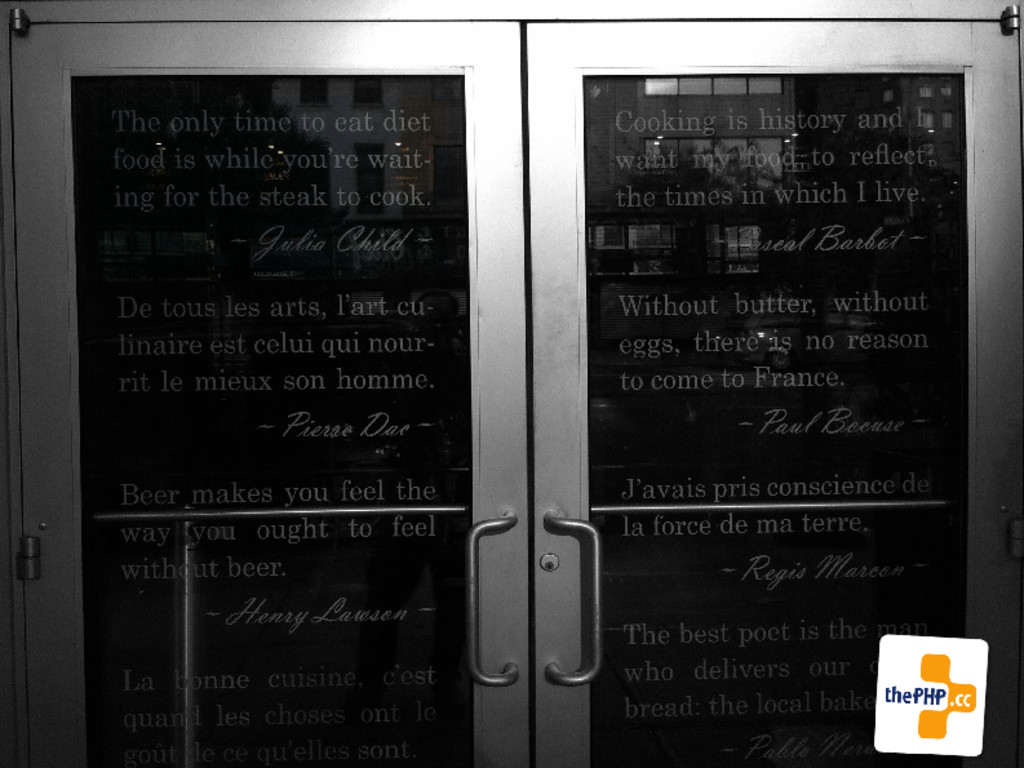

I would like to leave you with a quote from Julia Child:

The only time to eat diet food is while you're waiting for the steak to cook.

Bon appétit!

The slides used in this article were originally used in a presentation at the San Francisco PHP Meetup.

Deutsch

Contact

Deutsch

Contact